On Thursday, I was sitting in my car in the high school parking lot, waiting to pick up Matthew from his Speech and Debate team practice. I had my window down, and a car pulled in next to me. “Are you Diane?” I heard a woman’s voice say. “I am!” I said brightly, turning to her. I recognized her face from Facebook, but I didn’t know her name. She introduced herself and said compassionate things about Mark’s and my situation. She mentioned that she understood my intellectualizing in my writing.

Afterwards, I thought about what she said. Intellectualizing. I do that. I know I do. I do it because it’s what my brain wants to do, and it’s also a survival mechanism. Because from time to time, when I allow myself to feel the scope of this tragedy, for Mark, for his kids, for my kids, for me, it’s like inviting the tsunami at the horizon to advance. That dark line, from allllll the way left to allllll the way right. “Ready or not,” I could say, staring it down, “Advance!” I don’t choose to say that. Because I saw that movie, and I know how it ends: chaos, swirling debris, massive trauma, and lives lost. I have to function, and that wave is too freaking big for me to handle. Instead, I carry a big rucksack. I fill it heavier and heavier, sharing it with those who are willing to take a turn, and otherwise bearing what I have to bear.

How does this feel? It feels really, really hard. It feels very, very sad. It’s very, very heavy. I’ve been doing great with my Alive Tour, previously named the “Not Dead Yet Tour.” I’ve been forcing myself to engage more, plan more, experience more. I went to the Rolling Stones concert, took Mark to the zoo, and have said yes to more social things than I have in the last two and a half years. Which may not be saying much. “I’m feeling worse, somehow, now that I’m doing more,” I told my therapist last week. She wrinkled her brow. “That sounds like grief,” she said. Oh! I didn’t realize. Like the good student I am, I recognized that I had something to grab hold of. Grief work! Work! I could do this. I ordered some books. “It’s hard to find books that are about grief but not about someone you love dying,” I said to a friend. “The grief is about YOU,” they said. “Oh, I’m the one that died?” I said. “Yes,” they said. I understood. Mark is the obvious grief. On top of that, I am grieving the loss of me.

Some days I feel that more than others. Today, capping off a not great week, was one of those days. Today, my dad had surgery to treat recently diagnosed bladder cancer. My dad, who is my rock, my source of wisdom, my coach, my companion, and my co-conspirator in many a too-long bike ride in questionable weather conditions. He’s got cancer. I am carrying that in my rucksack. A few days ago, I took a long bike ride. I didn’t feel like it. A caregiver was watching Mark, the weather was adequate, and so I did it anyway. I pushed through hard miles until I hit the point, earbuds in and my playlist blasting, to where it felt good. I pushed more, pedalling harder, music pounding, until I started to cry. I cried for a mile or two, until the tears dried up.

Grief.

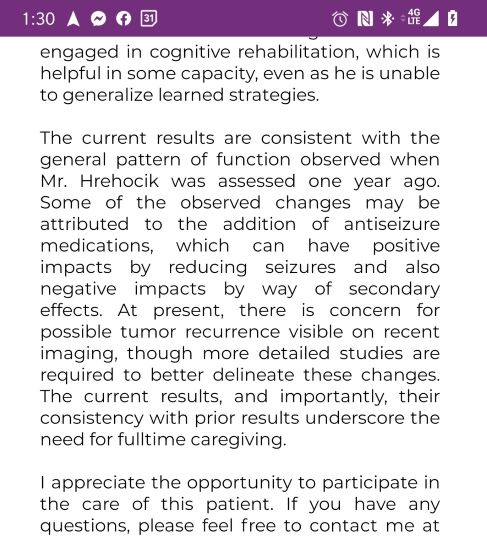

Today, I also read Mark’s recent neuropsychological evaluation report. I was waiting for this testing report, to give me a more objective assessment about Mark’s brain functioning. There were specifics on many metrics, none of them using any words above “average” and many of them using the word “impaired.” And then some hard hitting conclusions.

These are not surprises. I know these things, at some level. And yet reading them in print is a wallop, again. The consistency year to year means that how things are is how things can be expected to stay. Mark will never read these words, and he does not know the part that I already knew — that a recent scan is “worrisome” as the radiologist wrote. Could be something, could be nothing, and I know enough to know to control my emotions around the uncertainties. And yet it can’t not weigh me down. Getting through the days until we have more information is difficult. I haven’t told Mark; I don’t see the benefit in him knowing. I am carrying this burden for him.

“i carry your heart(i carry it in my heart)” E.E. cummings wrote. I remember plumbing that poem for its depths, as best in my complete earnestness as I could, as a young 20 year old. I understood then as much as I could, as much as anyone can before they start carrying anyone’s heart. Now I understand so much more. And I carry it. It’s a heavy, difficult, convoluted beauty and mess. Love.