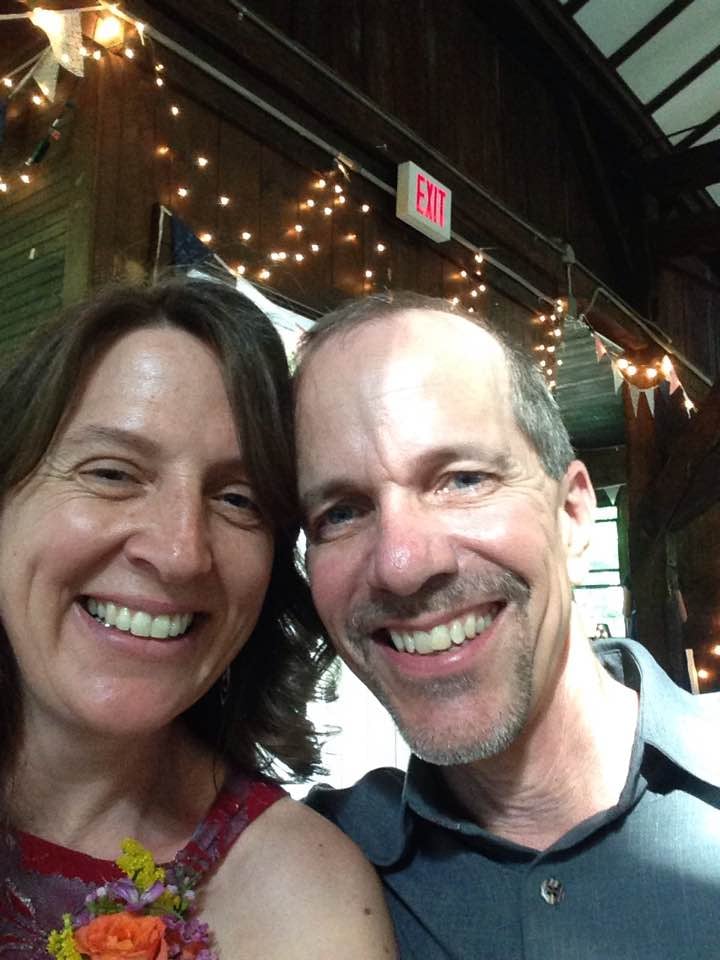

On Valentine’s Day, I decided to interview Mark. I looked up lists of questions you might ask your parent, or your grandparent. I didn’t know exactly what I was aiming for. Posterity? Connection? Understanding? I sifted through the options and picked out a few dozen. Over the course of the day, I sat next to him and asked him questions, recording the answers.

It was disappointing, largely. His remembrances were brief. His visioning is limited.

Perhaps, I thought, my idea of him “visiting,” and my expectations, needs to be refined. For me. Again.

Mark is six weeks post-surgery. They didn’t dig into his brain at all, and so while the surgery was significant and involved his head, he came out of it quickly and remains oriented every day. You know, as much as any of us in these pandemic-days. He knows the day of the week and the month and year. He knows the presidential scepter passed hands. He knows he has retired, and he’s accepted that the beaten-down old business shirts he still had from the 1980’s could go to Goodwill. (Sorry, Goodwill.) He’s tolerated the three antibiotics quite well, and they appear to be working. His weekly bloodwork shows reduced infection and reduced inflammation. PICC line is NBD now that we’ve gotten used to it. All systems go.

For me, in fact, Mark is so present that the finer detail of what it means for the big bad words to be in our daily lives is more important to understand. Encephalomalacia. Anhedonia. Osteomyelitis.

I study Mark every day. I watch him. I look up things. I am still worried.

He is here, and yet not completely himself. He is tired. He is either sleeping or lying down for about 18 hours a day. When he’s not laying down, he has three main activities: sitting and staring, eating ramen, working on a puzzle. Oh, and if it’s Sunday, reading the paper. Four main activities. For all his lethargy, he is still alarmingly unpredictable. This week’s excitement included him standing up from the couch suddenly one morning and declaring, “I’m going to go cut the limb off that tree.” In the spectacular wintery-winter we’re having, there’s six inches of snow on the ground. Mark weighs about four pounds, insists on wearing shoes that have no tread, and is cold all the time. If I ask him if he wants to go to the mall to take a walk, he usually says no because “it’s too cold to walk from the car into the mall.” Keep in mind we rock the best part of this whole lousy cancer process, the coveted “Disability Parking Placard.” And believe me, we use it.

And yet, his brain pulls these tricks occasionally. Focused on this task, Mark put on a jacket and hat. I hovered in the living room uncertainly while he rooted around in the garage. I have to mother him, I have to parent him, but when he’s this present, he’s aware enough to resist it. He emerged from the garage not with a small saw or loppers, which is what I expected, but with the giant tree pruner pole saw. A tall stick with a string that misbehaves and tries to trip you, with a toothed scythe at the end. He dragged it out the front door and onto the porch. I followed him into the front yard.

“What do you want?” he asked, glancing over at me. “I came out to see if you needed help,” I tried, not convincingly. “What I need is for you to not follow me,” he replied. I went back inside and watched from the window. Mark looked at the maple tree in his sight line for about one minute, then dragged the pole saw back through the front door. We live in the split level house built back during the Brady Bunch era, and the foyer holds approximately one person at a time. Matthew and I scrambled down to make sure the string dragging behind didn’t trip him and that the saw didn’t pierce through the screen door while we also didn’t interfere with Mark’s maneuvering down the steps to the garage.

“What happened?” I asked after he came back up.

“It didn’t look like what I thought it would,” he summarized.

I didn’t ask him any more questions.

When I texted Kim about it, she thought maybe I could have distracted him with an inside task. “I had!” I said. That morning, sitting next to each other on the couch as we do every morning drinking coffee, I had suggested he could help me count how many times the snow plow made a pass at our street.

I guess that didn’t work.

Sometimes little tasks like that do. For example, I told him two hours ago that I was going to start making dinner at 4pm. He has been busy eyeing the clock since. He just told me I was late getting started.

I continue to ask the internet for help. For my religious friends, I know prayer is a deep comfort and helpful. It is a comfort and helpful for me, too. Also I hope that God is up on social media, because it’s a much more rapid and clear response. Not that I’m not willing to go into the wilderness for forty days. That would be great, if God would send a babysitter for Mark and his kids. I’ll pack my gear right quick. Short of that, yet, I joined yet another facebook group today, the Osteomyelitis Support Group.

If you want to feel better about whatever you are not feeling good about in your life, join a support group. Someone always has it a lot worse than you. Actually, many many people. In my epilepsy group, people celebrate their tiny little adorable babies being one-month seizure-free. Through my SNUC group, I met a woman, who I now consider a friend, who is asking for prayers because her husband has a new lump on his head. In the Early-Onset Alzheimer’s group, people are agonizing about keeping their spouses at home or putting them in assisted living. While here I am, with a mostly fine guy, sitting on the couch next to me. Yes, he has a PICC line, and he needs to eat 100 hamburgers to gain more weight, and he really should not have tried going for a run two days ago, and he doesn’t show much interest in the world around him. Still, he’s stable.

Stable.

That’s our metric.

Today.

Through the osteomyelitis group, I have learned that this is a tough disease. Heck, I’ve learned it’s a disease. And a rare one, at that. I’ve learned that in Mark’s case, it’s a staph infection. I’ve learned that for many people, it’s chronic. It’s good it’s not MRSA. I already knew that. But it’s like, really, really good. I submitted the only post I saw about a skull. Other people are losing fingers and toes and arms. Toes are important. They change a life, a lack of a toe.

Is it helpful for me to read this stuff? Someone reading my writing for sure is asking this. Well yes, at times, it is. Probably not at 5am, which is when the osteomyelitis group accepted my request today, admitting me to their ranks. Not a great time to watch a 10 minute video overview of the situation, perhaps. But I do better with knowing, I do believe.

Because, here we are, three days away from an MRI that should have happened last week, except I cancelled because the weather called for ice. I have been watching Mark’s forehead for the last six weeks. Red, not red, red, not red. Every day, throughout the day. You’d think it would be easy to discern red from not red. Concerning from not concerning. It is not. Last week on Monday, I watched the weather, watched Mark’s forehead, and decided my risk assessment erred on road safety over learning — that exact day — if he was cured of this infection.

Besides, his IV antibiotics weren’t done yet. They are done this Tuesday. So.

I have become friends with Mark’s home health nurse, Carolyn. She is one of those amazing people who goes above and beyond. She comes once a week, but sometimes she texts me to see how Mark is doing mid-week. Sometimes, after I tell her, I get the magical, unnecessary, unexpected, and greatly appreciated text: “And how are you doing?”

Home health nurses. Who knew.

Carolyn tells me that symptoms or not (fever, red spot, etc.), the MRI could show infection in the bone. I have learned that there are only two options if the infection is present: more IV antibiotics or surgery. Or both. Three options.

The problem is it’s a skull. I get that losing any part of your body is something to adjust to, and it’s major.

You only have so much of your head to give. I really, really do not want Mark to have to have more surgery. I don’t want it for him, or for the kids, or for me, or for us. None of the things.

After the tree-not-trimmed episode, I checked in with Mark about his eyesight. I was trying to understand what had happened that he thought there was something to trim, and then not. “When you look at me, what do you see?” I asked. He took turns testing his eyes. His left eye: good. He looked at me, opening and closing his right eye over and over. Finally, he said, “You look black and white. And kind of fuzzy. And dark.”

Meanwhile, Michael, Matthew and I live in the house with Mark. In painful full color around him.

Did you ever build a fire? Box method? Teepee? Either one works. Pick your preference. Tinder, kindling, wood. Ignition. Sometimes the whole thing feels kind of precarious. I’m not always sure it’s going to work. When it does, it’s a moment of absolute joy. If I’m cold, it’s a moment of great relief.

Sometimes, to me, Mark’s situation feels like a tinderbox.

Whether igniting is good or not good depends on how you structure your metaphor.

At night, I sleep with my head on Mark’s chest. His heartbeat is continuous, and it’s incredibly fast. “It’s 90 bpm,” Carolyn clocks every visit.

At night, from his heart to his skin to my ear, this rhythm seems insistent, frantic.

We had a Zoom call with Mark’s siblings a few nights ago, for his brother’s birthday. Mark has a wonderful family, and I was glad for the opportunity to connect. The next day, I asked Mark how it was for him. “I’d rather have had a normal night,” he said. Our normal night of course being dinner, news, Jeopardy, Wheel of Fortune, bed. Like it’s a prescription from a doctor, it’s unvarying. “Well tonight should be a normal night,” I replied. “I wish you hadn’t said that,” he responded. “Why?” I asked. “Because now it’s less likely to be normal,” he replied. I paused, trying to assess. “I don’t have that kind of power, just using my words,” I said. “Yes you do,” he replied. Pause. “Do you?” I asked. “Yes,” Mark said.

The year of magical thinking, I thought, thinking of Joan Didion.

Mark loves his family. But this is how much we have to live in the moment. Encephalomalacia. Anhedonia. That’s how much hope, let alone future, is not a part of what makes our lives run.

“You can’t hope,” I observed. Yes, he replied.

“Well, let’s just stick with the moment we are in.”

Yes, he said

Okay, I said.

Here we are. Right on the edge.