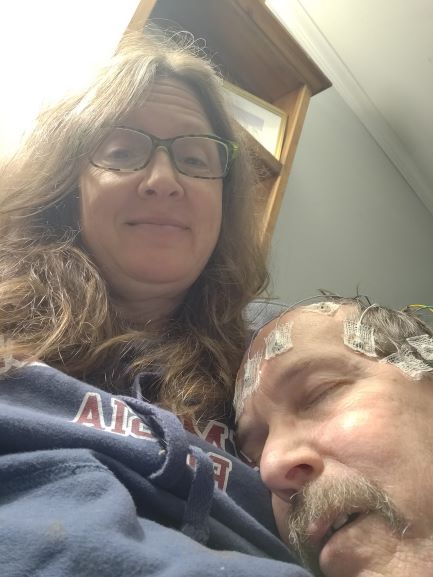

Mark is visiting. For the past two weeks, little by little, he has reemerged. Speaking a few more words. Noticing things. Asking questions. “You seem to be doing so much better!” I said. “I am better,” he replied with a smile, his dry sense of humor being part of what has returned. “What does it feel like?” I asked. He paused. “It feels like being more alert. I can do something and then I don’t have to take a nap afterwards.” That’s true, he is napping less. Maybe three naps a day instead of what had seemed more a life of continuous napping interrupted by being awake.

It’s wonderful. It’s also reminiscent of when your toddler transitions from taking two naps a day to dropping the morning nap. The nap they needed. The nap you needed. Poof the morning nap disappears. “Great news! They are growing so well and hitting all their milestones!” you think cheerfully. And then wonder how you will adjust. The hour you didn’t have to worry about them eating crayons or tumbling down the stairs. The hour you could clean, or cook, or read, or sleep. The hour you could just be.

Yesterday afternoon, while I was making dinner, Mark decided he was hungry right at that moment. He opened the refrigerator and retrieved his leftover deli sandwich, wrapped in paper, from lunch. He opened the oven, which was on because I was baking yet more nut rolls. Popped in the sandwich, paper and all. I took it out. “Mark, you have to take the paper off or it could catch on fire.” He looked at me like I was insane. The same “I’m worried about you” look he had given me the day before when I was wrapping stocking stuffers, a tradition in my family and something he sees as completely useless. “Gummy bears? You wrapped GUMMY BEARS?” “Well, not individually,” I said lightly. “Now that would be crazy.” He was unhappy at my intervention with his sandwich. “The paper can’t catch on fire,” he said. “Why not?” I asked. “Because there’s no oxygen in the oven!” he exclaimed. After dinner, I watched as he got the sandwich back out of the frig, again put it in the oven, paper on. He left it in for 30 seconds. Took it out. Took a few bites. Proving a point. I ate the remaining sandwich for breakfast the next morning. Removing the problem. As a parent does. As a caregiver must do.

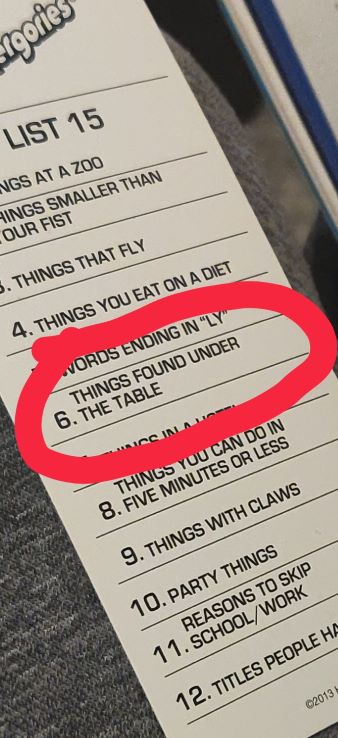

“What are you reading about?” I asked Mark at lunch the next day. He had spent an hour silently reading the Sunday Review in the Times. “Death,” he said. Later that day, I picked up the review section and sure enough, the entire front page was a wash of somber colors and in small font, the words, “What is death?” Way to hit 2020 on the head, New York Times. I opened to an essay exploring death written by BJ Miller, a prominent hospice doctor and author. He gave the unsatisfying medical and legal definitions of death. Then he urged us to explore the gaps in the cold certainty of those definitions, to explore how as we each must define what is life, we each must define what is death. When you can’t perform meaningful work? When you can’t interact with people around you? When you can’t take in simple pleasures? When you reach death, how will you know?

Oh 2020, what’s to be said that has not already been said? Mark has come to visit before in 2020. It’s a funny and hard thing that when he returns, my expectations of having a partner so quickly flow back into place. I’m so ready to accept a return to normal at every turn. I so quickly forget that a visit doesn’t mean a stay. It could. It might. It might not. Once, in 2020, when Mark had returned and in a moment of exhaustion and frustration with his almost complete inability to recognize or see my humanity, I blurted out, “My life used to be like this!” I threw my arms wide. “And now,” I said, “it’s like this,” drawing my hands together, holding my fingers an inch apart.

Not helpful, I know. We all have our moments where what we are trying to hold so carefully together cracks. Sometimes, like ice melting on a lake, the crack is resounding. It may all freeze up again, or melt completely. One way or another, life is always in transit.

In 2020, my world continued its shrinkage. I was not alone. The world joined me. We have all had to learn to live within our smaller confines.

Yesterday was the winter solstice. I took a walk. Snowy and icy, the bike trail was silent and deserted. Stress can drain you; it can also energize you. Like something rabid, I felt like I could walk to California. I headed west. I thought for a second, what if I slipped and fell and broke something? I kept going. If I needed to, I could crawl to help.

The first summer after Mark and I met, we decided to take the boys caving. We headed to the Laurel Caverns in the mountains south of Pittsburgh. Our relationship was still new; I had met these boys only a couple times, and I worried that they were so often quiet, so often inside, so clearly marked by their mom’s death only two short years before. I hoped to get them outside, engaged, exploring, seeing all that life can bring. We decided to skip the self-guided, lit tour of the cavern and instead signed up for the guided tour, actual spelunking. Helmuts and flashlights on, I had a moment of fear as the guides pointed to a slit in the rock I hadn’t noticed and led us through. “This is fun!” I said brightly, worrying that this was actually not fun. Down down we went, winding and climbing. Optional belly crawls through cold creeks. “This is fun!” I kept thinking. I clambered over a boulder. Stepping down off it, my foot twisted and a blinding pain shot up my leg. I cried out. I thought I had sprained my ankle. The guides came over. I tried taking a step. I couldn’t put any weight on it at all. Toughness is my thing. Making it through is my thing. Holding up an entire group because I can’t do something is not my thing. I had no choice. The two guides conferred. One would continue ahead with the rest of the group, the other would run back up through the cave to the lowest point that a phone was wired, call for help, then wait for the rescuers to show up and navigate them to where I was. Everyone left. I sat. In the total silence. Thirty stories underground. And waited. I thought about life. I sang songs. I recited the 23rd Psalm. I thought about the part of the planet I like, which I decided was the on-top part, not the inside part. I turned off my flashlight to conserve the batteries. The utter darkness was too scary. I turned it back on. I had no sense of time. I knew I could never get out on my own. Eventually, three rescuers appeared. Where the cave was wide, I held on to two of them and hopped. Where it was too narrow, one slung me over his back and carried me. Where it was too short, I crawled. Where it was too steep, I sat holding my foot up carefully while they hauled me up backwards. Hours later, filthy and exhausted, we emerged. They brought me a soda, one of the best sodas I have ever had in my life. “Well that was a fiasco,” Ben said quietly as I hopped back to the car. Indeed. For the next year, I recovered from what had turned out to be rupturing my Achilles tendon. Alma’s senior year of high school played out to include my surgery followed by many casts, a walking boot, crutches, scooters, and physical therapy. I hopped through college visits, a day trip to the beach, a winter interview for Alma at a college a nine hour drive away.

I have crawled to help enough in my life to know I can do it.

I have a dear friend whose life has exploded, in a way different than mine, and yet we can find parallels. The lack of control, the uncertain future, the days of shock and sadness and leadened bodies giving way to days of energy and hope and possibility. And then back again. The yo-yo of it all. For her, the metaphor of walking a tightrope is meaningful. The careful balance with an eye on the next platform. I thought about this as I walked on the icy path yesterday. My metaphor is a mountain. I am climbing, climbing, climbing. I am pulling Mark up with me. We have reached a little ledge, not visible below. Now that we’ve arrived, I can see it’s big enough for us to bivouac. How long can we stay? What is up above, hidden in the clouds?

A few weeks ago I had a dream that the day after the winter solstice, the sun came out, the grass was green, the flowers were blooming. It was spring. It will take longer than a day for that to happen, but today there will be a little less darkness than yesterday. And on and on. Until six months from now, when the yo-yo will flip and we will head the other way once again.

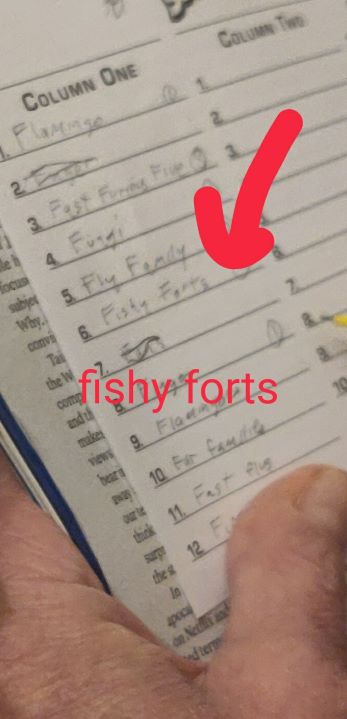

For years, my college friend Sherri has been living in South Korea and teaching neuropsychology at a university. She asked if she could record an interview with me via Zoom to show to her students as a way to bring to life the impact of a brain injury on a person and their caregiver. “You’ll want to speak slowly, English is the second or third language for many of the students,” she advised. We recorded the interview. A couple weeks, later Sherri sent me their written responses. They were kind. So kind, so generous, so caring. “It was interesting to know that even though it is a disease on sinus it can go into brain and that will damage the patients thought or cognitive process. It is somehow scary that one disease can cause so many other problems and disorders. Also if there is anything suspicious about body go to the doctor before it gets worse. God Bless Mrs. Diane and Mr. Mark hope they will have a blessed and loving life!” And some, so funny. “I would like to learn about the Caregivers Roll. Is that like a somersault?” Yes, many many somersaults. Often not the kind we learn in kindergarten on a flat mat in the gym. Often not the kind children do on a warm summer day down a flower-covered hillside.

I thought about my little inch of life during my walk yesterday. It was around mile four of what turned out to be a nearly seven mile hike. Perhaps it was the endorphins that had kicked in. Perhaps it was my playlist bringing up Miley Cyrus’s “The Climb.” Perhaps it was the glorious snow. The red and blue flashes of cardinals and blue jays in the bare trees. The momma deer and her two toddlers grazing by the creek, as I ate my apple and watched. Whatever it was, in that magical moment, I was pretty sure that in 2021, I can take that one inch and bedazzle it, explore every space within it, walk when I can, crawl when I must, find the energy in the darkness and in the light.

Mark is visiting. The caregiver rolls on.