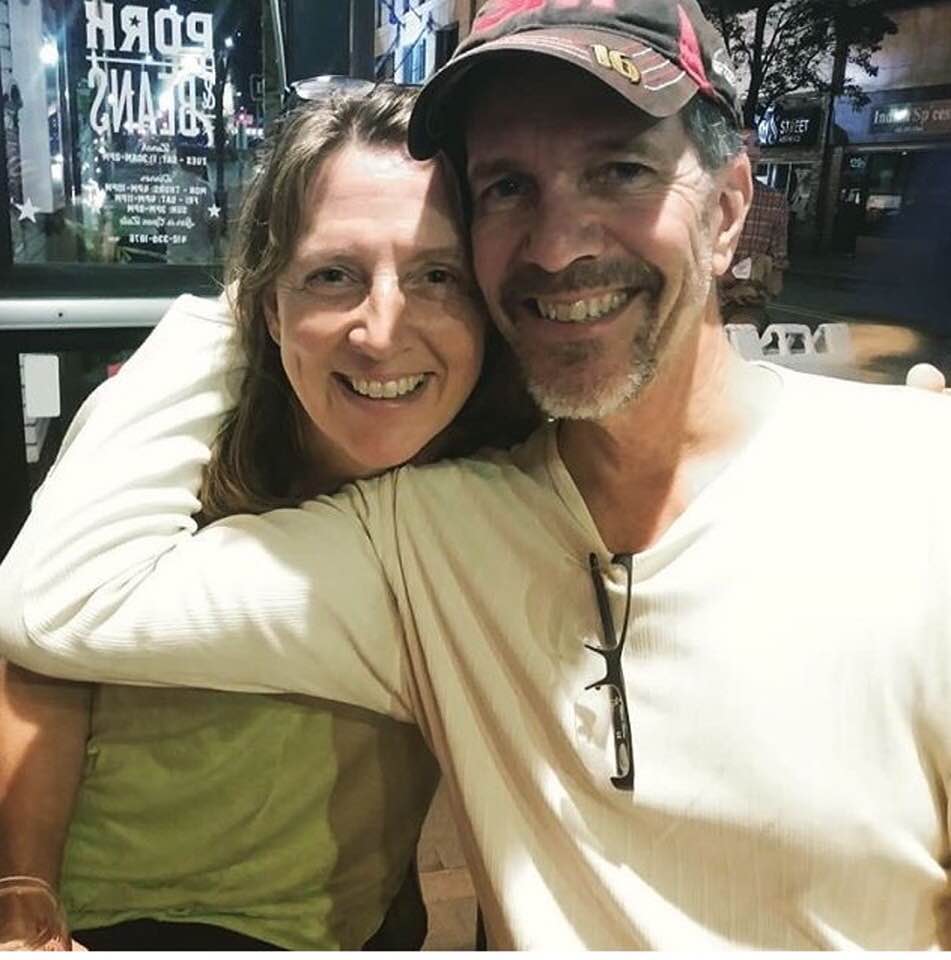

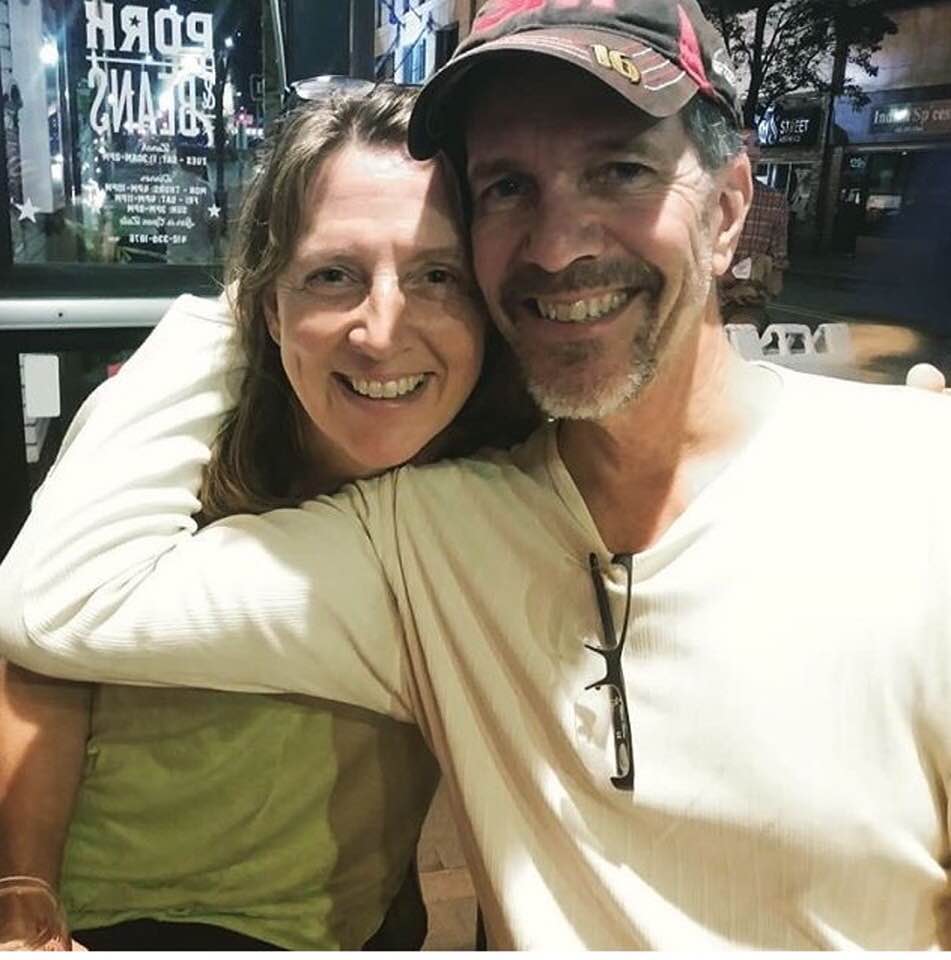

Missing this guy tonight…

Living and loving life (most days), despite SNUC (Sinonasal Undifferentiated Carcinoma)

Missing this guy tonight…

I had a dream last night that I was sleeping underneath a blanket & a grizzly bear came and laid on top of me. In my dream, I woke up and thought if I stayed very still, maybe the bear would not maul me to death.

I’m not in expert at dream interpretation. I wonder what this means?

Day 21 ends with Mark being placed! Finally. Moving to a skilled nursing facility. This has not been an easily won battle. Mark’s been ready, the docs say, to be discharged for a few days. Hospital social workers have been trying to find a skilled nursing facility that will take him. I think of them as The People Who Know Things. They’ve been trying to bring me up to speed on how this massive part of the US health care system works. The problem seems to be Mark’s combination of needs. He’s still confused and being guarded by a sitter to keep him safe. The People Who Know Things tell me the only option for keeping him safe once he’s discharged to skilled nursing is to be placed in a locked unit, and the only kind of locked unit is dementia.

This sounds both terrible and great. It’s great because once Mark got out of the neuro ICU, which is locked, the next units he has been on are unlocked. Surprisingly, for the fact that this is the major trauma hosptial in our city, there’s almost no security other than in the ER. You can walk right in, take the elevators up, and walk into the units without ever saying hello to a single staffperson. That also means that Mark could probably figure out how to make it to the elevators and end up anywhere in the hospital, or out of it for that matter, and it’d take a long time to find him. I like the idea of him not being able to get lost or escape.

The People Who Know Things are having a hard time getting Mark a placement. They ask me for parameters. They print off lists and ask me to prioritize my choices. I’ve heard of none of these places. The print offs are from internet searches and they have star ratings. What do these mean? Not much, the People tell me. They take my random rankings and make calls. Rejection, rejection, rejection. We move from facilities within 5 miles to within 10, then 15. T “Why won’t they take him?” I’m trying to understand. The People tell me that they don’t want to take someone who is not only needing rehabiliation from brain surgery, but who also has to be go to chemo. Facilities don’t want to cut into their bottom line by having to transport Mark to his many trips to the hospital.

Yet another list of options is generated. One social worker points to the name of a facility and says, “My dad was in this one. It was good.” Okay, I said, making it my latest top pick. She called, and miraculously, they said yes. We had a placement. Within a day, Mark would be transported by ambulance to a skilled nursing facility.

Okay, you have to get yourself in the mindset of someone whose life has been chaotic and terrifying for three weeks to appreciate this. Where gallows humor is one of the ways to survive and persist through the muck of sadness and complex medical care. My dear friend Kim, whose gifts of humor and intelligence know no bounds, wrote a rap that captures the essence of the current experience. Key to appreciating it is knowing that Mark has been a tad non-compliant, and that docs call skilled nursing a SNIF and that the cancer Mark has is called SNUC. Thanks for the LOL, Kim!

I feel so stuck

since I contracted this SNUC

going to a snif

hoping to avoid cDif

sick of my pic line

wanna be online

really not feelin fine

wanna see sunshine

optic nerve? not doing well

need a nurse? i refuse to ring the bell

gotta babysitter

restraints and the mittas

No to the sodium

wanna yell from podium

NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS

IF I GOTTA HEART!

Kim’s song is much better than the poem I wrote last night (apologies to my mom and dad for cursing AGAIN):

Oh snap!

Mark has SNUC

And now we’re F*****ed.

Hospital dispatch: Day 18 in the neuro ICU. I’m giving a shout out to every doctor, PA, and nurse who’s treated Mark from neurosurgery, otolaryngology (it’s a learning opportunity–look it up!), Oncology, pulmonology, and any other -ologies I am forgetting. Also speech, PT and OT. And the case worker. And nutrition and housekeeping and security. And the parking attendant who is the most dapper dresser with the sweetest smile everyday. And Annie, my new friend from the waiting room in the neuro ICU who has laughed and cried and talked with me for weeks as she worries and waits for progress with her mom. I’ve been dropped into this complex community during this truly horrific time, and I’m so grateful for all these people.

Part of daily challenge is the total lack of control we have as the medical world swallows Mark up. We are waiting for tests, waiting for answers, waiting for treatments. I wait for Mark to wake up. I wait to see how much of him is going to return. Knowing Mark has cancer living in his head, it’s frustrating to wait for his body to be well enough to start chemo. I obsess over all those devilish cancer cells racing to multiply and invade new spaces. Each day without the chemo feels like we could be losing the race.

Mark was finally cleared for chemo yesterday. He had his first treatment today, the first of three days in a row on, 18 days off, that is the planned protocol. He tolerated his first treatment well. Meaning, my fiesty fighter didn’t fight it. You’d think with him having consented to brain surgery that it’d be no concern that he’d allow chemo. But Mark remains true to form and even with cognitive deficits and sleep aides, if he’s alert enough he picks and chooses what he’ll consent to. Yesterday, the nurse came in and handed him a little cup of his morning medications. “What’s this one?” he said, pointing to a small white pill. “It’s a sodium pill,” she said. “I’m not taking that one,” he said, and then took the others: anti-seizure pills, pain pills, anti-anxiety pills. Him saying yes to anything isn’t guarenteed.

To be fair, he still seems fairly confused. He often doesn’t remember one hour to the next. He doesn’t remember who came to visit him yesterday. The remote control for the TV doesn’t mean anything to him, he can’t use his cellphone, and the call button for the nurse remains a mystery.

Last year, I bought an Alexa. We didn’t have a stereo system, and I wanted a reliable way to play any music I wanted in the house. I had tried a vareity of small speakers with bluetooth and wasn’t satisfied with any of them. Mark and I often spent evenings taking turns asking Alexa to play songs. Mark loves music, and knows the lyrics to many songs across genres, starting from about 1940 and excluding most of the pop world of the 2000’s. One of the saddest moments from this past spring, as Mark plunged into sickness, was when Alexa stopped being able to understand him. His nose was permanently clogged (by tumor, we now knew), and when he was tired he slurred his words like a drunk. Now, from his hospital bed, as the equipment beeped around him day and night, Mark would call out over and over “Alexa, stop!” Alexa still wasn’t listening to him. He was patient with her. He would give up, fall alseep, wake up, try again.

Mark spent 21 days in the neuro ICU before being discharged first to the neurology unit and then to oncology to wait for chemo to start. Mark’s body was slowly getting stronger, but one thing remained the same: Mark was a pretty bad patient. This wasn’t a huge surprise, as he was a pretty bad patient before he ever got to the hospital. At one point last spring, I answered the house phone and was told that Mark’s cholesterol was elevated. “They want you to start on a statin right away,” I said. “I’m not doing that,” he shot back. At this point, he had already stopped taking his dilantin. I knew it was useless to argue.

In the hospital, Mark continued to be difficult. Before he had even opened his eyes after the surgery, he was working on getting his restraints off. In addition to the restraints, he had mittens on both hands so he couldn’t use his fingers. He was surrounded by equipment keeping him alive, but the primitive “fight!” part of his brain was doing great. He’d work until he’d exhaust himself out to get these restraints off, a few minutes at a time, sleep, repeat. One day, he finally achieved success. His sister Marcia was visiting, and we were standing on either side of his bed. Mark started working on his restraints. We gently laughed at the impressive survival response. Then suddenly he got one mitt off. Marcia grabbed one arm, I grabbed the other, and he somehow STILL was able to use his one free hand to pull the other mitt off. He immediately went for his head, which was covered in drains and a ventilator and about 100 stitches holding his skin together. We held, I yelled, and Mark was able to get his hand to his ventilator and begin pulling. He began coughing out clotted blood as the nurses ran in and Marcia and I backed away, frozen, staring at him thrash. Marcia grabbed my arm and said, “Let’s leave. This scene will be burned into your brain. You don’t need to watch this.” I let her lead me out. She was right.

It should not have come as a surprise when I came into his room one day and the nurse told me he had pulled out his PICC line. Mark was awake sometimes could communicate a litte. I asked Mark, “why did you do that?” He said it was an accident. The nurse held out his arms and demonstrated how long a PICC line is. Not an accident. A few days later, I was told that Mark had pulled out his lumbar drain overnight. I was afraid he was going to hurt himself. They added in medications to keep him more sedated.

Once he got downgraded to the neurology unit, Mark maintained the fight position. His baseline in life is not wanting help. With the recent brain surgery, his poor vision, and challenges with balance, the doctors labelled him a fall risk and insisted that he get help getting out of bed. It was unclear if he understood what the call button was, or whether he just refused to use it. One night, I called the nurse’s station to check on Mark. They connected me to Mark’s nurse, who said, “He’s being difficult. In fact, he’s standing in his doorway right now. Sir! Sir! I need you to go back into your room.” I heard Mark mutter “No.” The nurse asked me if I could talk sense into him. I said, “If I could have talked sense into him, we wouldn’t be in this position right now.” The nurse kept me on the phone and I heard him say, “Sir, I’m on the phone with your wife right now and she wants you to go back to bed.” I heard Mark slur out “I’m sure she’d like me to do a lot of things.” I hurried off the phone, and laughed for a long time at Mark’s fiesty spirit. After a few of these incidents, the hospital posted a “sitter” in Mark’s room 24/7 to make sure that Mark stayed put.

For as much as I was terrified that he’d hurt himself, I also could appreciate his desire for autonomy in a situation in which he completely lacked control. Within a couple months, he had gone from a man who happily went to work, took care of a house and a gaggle of kids, paid the bills, andran at lunch time, to a guy who was not allowed to walk into the bathroom alone. I’d rather he fight than give up.

Finding beauty in the Neuro ICU waiting room.

The waiting room in the Neuro ICU is intense. Everyone in there looks strung out, like some disaster has befallen them and they haven’t bathed, eaten or slept in days. Which, to be fair, is probably true. They are there because someone had a stroke, or a seizure, or a fall, or a little cancer in their brain like Mark. No one’s sitting there hoping that the knee replacement went okay. They are there, sitting in sheer terror, wondering if their loved one will emerge the same, or alive.

There are many hospitals in our city. The one we are in is the main trauma hospital. It hasn’t fully caught up with more cushy models of newer hospitals. When you leave the flashy lobby and find your way into the recesses of the hospital, it’s pretty bare bones. A few uncomfortable couches and chairs. No magazines or books. A TV without a remote control. Armed cops in the hallways guarding prisoners who’ve come in the medical treatments. The main thing it has going for it is the beautiful view of downtown. And a medical community with a great reputation, which is all I cared about.

The first time I sat in the Neuro ICU waiting room was the night of Mark’s surgery. The main surgical waiting room, a windowless basement affair, had closed up shop for the night. One by one throughout the evening, cases were removed from the monitor until Mark was the last case listed, with “In surgery” still indicated. My parents and I took the elevator up to the 9th floor to wait in the Neuro ICU for the surgeon to emerge and hopefully tell us everything went well.

The waiting room was empty when we arrived. A stack of blankets and pillows was wedged into a nook near the windows. I grabbed one of each and found the light switch to darken half of the waiting room. I curled up on a two-seater plastic chair to try to sleep.

Soon, a woman came in talking at full volume on her phone. My dad gave me a look, and my mom gave my dad a look, and I said, “It’s fine, dad.” He waited a few minutes, and then went over and said, “Excuse me. My daughter is trying to sleep. Her husband is in surgery and we’ve been here for hours. Could you talk more quietly?” She gave a half-second stare with a pregnant pause, and said “I’m sorry about your daughter, sir. My daughter is unconscious and has been here for 5 days. I’ve been sleeping here for 5 days.” It was her stack of pillows and blankets we had pillaged unintentionally. My dad tripped over his words to apologize and wish her and her family well. We settled back into our respective waiting room activities.

Over the next days and weeks, I met some wonderful people in that room. That woman was one of them. She was absolutely distraught. Her daughter, a 36 year old mother of one, had suddenly collapsed one night. She was not improving. Her mom went throughout the day went from sleeping to crying to arguing with the nurses and doctors about her daughter’s medical care. She actually almost never went in to see her daughter – she said it was too painful to see her on a ventilator. One day, she was told her daughter would die and that it was time to take her off life support. A a dozen family members came into the waiting room to wait, and to say goodbye. I hugged her and told her I was so sorry as she sobbed “That’s my baby they are talking about!” She was angry. She wanted more to be done. The next day, she was told they could operate on her daughter to try to stabilize her, and this mom was again raised up on a tiny balloon of hope. By the time Mark was discharged from the unit, 21 days later, she was still hoping and praying.

I made a dear friend in the Neuro ICU waiting room. Annie was there everyday, in her blue sweatshirt and shorts. Her mom, in her 70’s, had fallen and hit her head. A scan revealed a benign tumor, but her platelets would not stabilize. Everyday the doctors tested and tried new things, but nothing would stop her body from destroying the platlets that they kept giving her. Her dad, a local cop, would come in between shifts, worry lines etched on his stern face. “What am I supposed to do?” asked Annie, who lived out of state and had a family of her own to take care of. “What am I supposed to do?” asked her dad who held down three jobs. Annie taught me how to arrange the chairs for the most comfortable nap. I brought Annie food when she wasn’t eating. When the ENT surgeon rounded on Mark, Annie was the first person I told what I had heard. Stage 4, rare, aggressive, poor prognosis. “This is so fucked up,” she said. We said that a lot to each other over the weeks. We texted each other late at night and saw each other the next morning to do it all again.

In a way that is difficult to convey, there was a beauty in the starkness of what life became during those weeks. A tiny community deeply bonded together by trauma showing us exactly how powerless we are. Every story in the Neuro ICU waiting room was distinct, yet our fears were held in common. We didn’t know where the line was between life and death for our loved one. We had to confront questions about quality of life. We had to learn patience or we’d fry our brains in anxiety and fear. We had to hold on tight to each other, riding the waves that came ceaselessly on a dark horizon.

Mark’s surgery lasted until late in the night. I went back to my friend’s house and slept a few hours, and then took a Lyft back to the hospital. On the 15 minute drive, the Lyft driver was chatty. “What’s taking you to the hospital today?” he asked. “Well,” I said, “You are taking me to the hospital to see my husband for the first time after he’s had brain surgery. I’m not sure if I will be able to recognize him. I’m not sure what he’ll look like.” “Oh, okay,” he said, speaking carefully. “I hope everything is okay for your husband.” I remembered how early in my relationship with Mark, when I’d tell him something that was worrying me, he’d say “I hope it gets better.” After a few of those responses, I told him that this generic statement back agitated me. It then became a joke. I’d tell him something like, “I’m worried that Alma is depressed,” and he’d lightly say, “I hope it gets better!” I could see now that he had used this phrase because sometimes, when faced with something that is so far beyond our control, all you can do is hope for a good outcome.

Mark was recognizable. I’m not sure how you can remove part of someone’s skull, do some patch work to replace eroded bone, and then zip them back up to look pretty much the same, but they did. “The swelling and bruising will come,” the surgeon warned. But it never did. He looked like Mark, hooked up to a lot of equipment, with a stitched incision travelling over his head from ear to ear. Monitors beeped and urine output was checked and the ventilator helped him breath. Nurses and doctors moved quietly in and out all day long. A sign on the door warned visitors to put on the blue plastic gowns and gloves because Mark had a tiny bit of MRSA residing in his nose. He was asleep. I could sit there and hold his hand, and other than that, I had to wait to see how he would be when he woke up.