Merriam Webster: The state or condition of being a survivor; survival

Macmillon Dictionary: Sorry, no search result for ‘survivorship.’

Oxford English Dictionary: Get your annual subscription for just $90!

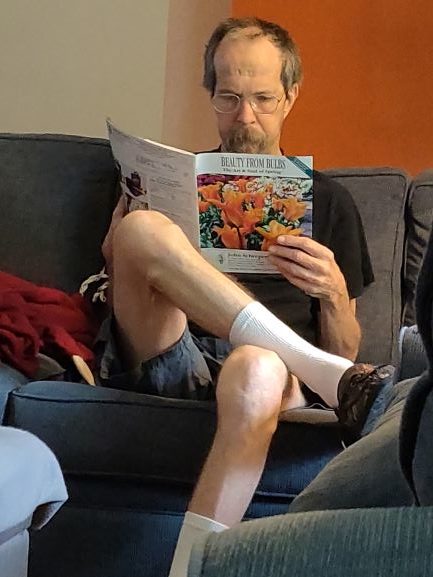

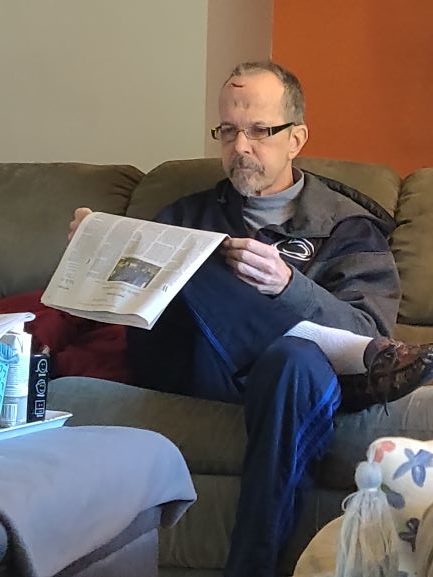

After all the “all clear!” moments have passed, we are left with surviving. Mark has been referred to the “survivorship clinic” for head and neck cancer. It is not clear what this means, because he’s six weeks clear and six weeks from the next scans. We know it means this: he’s surviving. He has side effects, and he needs to cope with them. Dental, vision, hearing, nutrition, swallowing. Some could improve, some are left to manage longterm.

While all eyes may be on Mark, I’ll say that it’s not easy for me, either. I’ve been watching “Alone,” a History channel gambit at the reality TV genre, in which individuals try to survive alone in the wilderness with their ample skills matched with their ample willpower. From what I’ve seen so far, they mostly end up starving and giving up within three months.

I can tell you this: Mark and I are surviving. I can also tell you that the current world we live in feels so little like the world we’ve come through. Starting with this surprising observation: visiting Mark in the various ICU and hospital and skilled and rehab and senior living places he’s been in the last eleven months always included a level of stress, of course, but also always included a level of community. I never, ever felt alone, even while I often felt scared. There were friends and family with me so much of the time. There were total strangers in waiting rooms who, like me, wanted and needed to talk. There were doctors and nurses and other practitioners who had a few moments or more to give to the problem set before us: Mark’s heath.

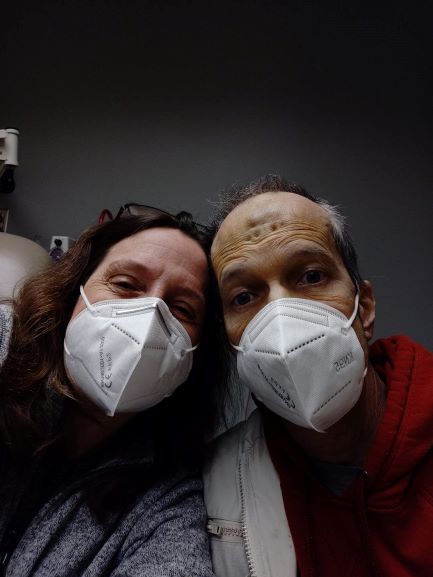

Last week, I went with Mark to a standing appointment with his oncologist. At the entrance, after measuring our temperatures as the only check of our health, they let us both in. They did not, however, let me into his lab draw. They pointed to an atrium and promised me they’d find me there. “How will Mark know where I am?” I said. “We will find you,” they replied. And so I went and got a coffee and sat in the atrium, watching videos on my phone and hoping they were right and they’d find me. Less than six months ago, I would have been at his side, interacting with him and the nursing staff throughout the entire appointment. I would have gleaned new information about his health; I would have asked questions that would have helped me gain a little bit more knowledge about the human body. Alone, back in the atrium, two hours later Mark’s oncologist’s nurse practitioner, Avi, came out to report how the visit went. And then we went and found Mark, ready to go home, together.

Now, if you’ve not been following along through this journey, this all might seem insignificant. However, for the past year, I’ve been attending to every detail of Mark’s life, as he has not been able to. The idea of him being alone in any setting has been incomprehensible, because Mark has not been able to comprehend any setting he’s been in for most of the past year. Me hearing how he describes his health to medical personnel has been valuable, as I learn what he is experiencing and I can correct things he is not conveying accurately.

The time I’ve spent in the hospital with Mark over the past year — whether he’s been inpatient or outpatient — has been significant. It also has not been lonely very often. Hospitals have a sense of community about them. There’s an overall spirit of “we can do this together” that permeates the staff and the visiting families. You have strangely beneficially conversations in line in the cafeteria. Someone says something randomly nice to you in the elevator. The nurse lingers to make sure you understand some part of your loved one’s care. Layer a mask and Covid-19 fear on all that, and the hospital has become another place of isolation and sadness. Families waiting in the atrium for a practitioner to emerge sit in silence, masks and ear buds and screens all a barrier to connection as we wait.

It is impossible for me to imagine how this past eleven months would have played out in the current reality of today. Last August, when Mark was in brain surgery, I had a crowd — parents, friends, sisters-in-law and niece — come and stay with me in the waiting room. They brought snacks and games and wine and distractions. They fed me and made jokes and sat quietly and encouraged me to nap. Strangers dwindled out and my support network thinned but never disappeared. I can’t image — I cannot imagine — what it would have been like to not be surrounded by love and support while Mark’s skull was literally being removed and a tumor excised.

I cannot even comprehend how our world has changed. I can’t comprehend how what I went through happened, and how I make it through everyday.

I do. Mark does. We do. It is not easy. It’s not the hardest it could be. But it is hard. Somehow, we survive.