Mathew, the baby of the family, turned seventeen last week. The day before his birthday, I reminded Mark that we still needed to buy Matthew a card. “Oh yes!” he replied enthusiastically, “Let’s do it tomorrow.”

At noon the next day, I carefully said this: “Would you like to go shopping for Matthew’s birthday card before lunch or after lunch?” Every parent will recognize this sentence construction, as will every caregiver to someone with dementia. These two things are happening. The freedom offered is limited to the order of events. This strategy works with Mark quite often.

Not this day.

“You can go,” he said, glancing up from the Sunday Times. He had been reading for hours, sustaining attention at a level that indicated more perseveration than interest.

The boys were not home to watch Mark, so the only option was to run the errand together. “Well, I don’t want to leave you home alone because of your seizures.” I kept my tone friendly and even.

“It doesn’t matter.” Mark turned back to the newspaper. I knew better than to pursue it. Whatever circuitry normally keeps Mark’s fatherly love intact was temporarily disconnected. Matthew’s card would remain unpurchased.

Despite all I’ve learned about Mark’s medical conditions over the past three years, if a doctor scheduled a dry two hour long public PowerPoint lecture on his case, I’d still feel the driving need to attend. In other words, I get it and I don’t. Brain circuits turn on and off, terrifying problems wane and then evolve into new potentially catastrophic concerns. My friend Janet’s voice from three years ago echoes in my head: “Once you get on the conveyor belt, you never get off.” She was so right. That conveyor belt continues to the vanishing point on the horizon.

For the past few months I’ve had writer’s block. What was there to say that hadn’t been said? This journey would go on, it would have ups and downs, the details would shift and anyway, did the details even matter? Overall, Mark was happy. “Every day I exceed my life expectancy,” he mused. No one could argue with that.

Pleased with his happiness and a miraculous timespan when the medical world took a backseat, my head grew tired of the mining for understanding and meaning. I turned off the microscope and lived within the daily realities rather than continually manipulating the lens to try to clarify the view. I relished solitary winter hikes, endless hours of staring at gray skies and even grayer trees, the ebb and flow of kids coming and going for holidays, napping at all hours with Mark curled up asleep next to me.

Nothing was wrong.

Nothing was really quite right, either.

Eventually, I started pouring my documentarian urges into social media. It required less energy than writing, and I appreciated exploring visual story-telling. I began posting in earnest to the big two, Instagram and Facebook. I realized that recording elements of my days felt like bringing people along with me. I posted photos and videos of taking Mark out to lunch, to PT, to hospital appointments. I documented plants and muskrats and meditations on flowing water. I felt less alone in my love for and worry about Mark. Others bore witness. Our family. My kids. Old friends. New friends. Strangers.

I followed posts of other caregivers managing loved ones with dementia, traumatic brain injury, cancer, etc. The Meta-verse swelled to a net positive for me, this virtual world that understandably is often demonized as life-sucking. But in my world of near complete isolation, social media provided me with figurative windows that became literal doorways. The common language developed through unique experiences was connecting, in a life that felt completely disconnected from anything I had ever understood as “normal.” The words of these strangers made sense.

I love her more today than I ever have before.

I don’t know how to get through today.

Every bit of exhaustion is worth it to have these memories together.

My sitter called off and I’m going to lose my mind.

I wouldn’t choose it any other way.

I miss my husband.

There are good things about this life.

I miss me.

The caregiving crowd deeply understands “one day at a time,” bravely sharing the utter exhaustion, chaos, fear, loneliness, worry, and melancholy that accompanies every little good thing we somehow manage to snatch from the very thin air.

Early in 2022, while I was busy watching snow fall between naps, the medical focus on Mark slowly transitioned from cancer and tippiness to his propensity to be seizurey. While no one uses the word remission yet and he’s still tippy (but much less so), Mark’s seizures have ramped up. In fact, he’s had seizures every day for the past three days. The past two nights, I laid awake and watched his sleeping body, his face, hands, arms and legs twitching for many minutes at a time as the seizures came in clusters. This morning while reading the paper, Mark started spewing random words. I sat next to him. “Are you okay?” He smiled back at me and nodded. “I’m making you eggs,” I said, apropos of nothing. He nodded again and went back to reading.

It’s easy when talking about disease and treatment to tack on “the worst!” Cancer is the worst! Chemo is the worst! Radiation is the worst! Dementia is the worst! I’m not into competitive suffering; I think each and every one of these things are THE WORST. So to give seizures their due, I declare them to be THE WORST and will address them directly.

First, Seizures, a little warning would be nice. Or maybe a schedule. You can come between 4-5pm on Mondays and Fridays, and never in the middle of the night.

Second, a sense of what causes you would be welcomed. You know, so we can make informed choices. Is one cup of coffee okay with you, but not two? How do you feel about crowded waiting rooms? Watching TV?

Finally, if you could choose a singular demonstration of your power, that would be cool. You have choices: muscle spasms, word scrambles, staring without responding. Grand mals are a nonstarter, obviously. And I would like to remove from the table the option of dead falls when standing. Those are always inconvenient.

A dead fall most recently happened in February, announced by a thud from above while I was downstairs. Running up from the basement, I found Mark on the bathroom floor, his nose a bloody new shape.

“Hey buddy, you broke your nose,” I frowned, crouching down next to him and grabbing a towel. “We’re going to have to go to the hospital. Do you want me to drive you, or do you want to take an ambulance?”

“You,” he said.

“Let’s try to get to the couch,” I said, grasping his elbow. Mark struggled to stand, then struggled to make his legs walk. I ended up holding him around his waist from behind, propelling his body forward with mine. I slid onto the couch and pulled Mark down on top of me. After I skittered out from under him, Mark remained where he was – slumped, dazed, bleeding. He had fallen directly on his face, and I realized he also had a deep gash over his right eye. Living without his full skull, I worried about his brain, his grafts, the reconstruction of his sinuses. I called 911.

As happens, the police arrived first. “Have you been here before?”I asked the young officer. In other words, how much do I have to explain to you? No, he replied. I told him about Mark and what happened. He checked out the bathroom like it was a potential crime scene.

“Did his head look like that before?” he nodded at Mark’s forehead.

Umm yeah buddy, AS IF I’d calmly tell you my husband has a broken nose after a seizure, but leave out that his head was also newly caved in.

The ambulance came, the EMS folks scolded me for not having Mark’s med list on the frig, which for sure I should, and off we went for another long day in the ER.

In March, Mark returned to the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) for another attempt at intentionally inducing a seizure while on continuous EEG and video surveillance. During his August EMU stay, Mark lasted eight days with no seizures before we gave up. This time, Mark had four seizures within 24 hours of being off his meds. Two were focal, one progressed to grand mal, one happened while Mark’s cousin Drew and I were talking to him. Drew and I had no idea Mark was even having a seizure. Mid-conversation, a tech and doctor came running in, peppering Mark with orientation questions and examining the EEG monitor. “Is the crash cart outside?” I heard the doctor whisper to a nurse.

Mark answered all their questions correctly despite his heart rate hitting almost 150 and his brain waves going bonkers. They injected him with a radioactive tracer that would light up his brain in a scan to show where things were going haywire, which was the point of this whole exercise. Then they injected him with a seizure rescue medicine. That afternoon, the doctor restarted his meds and two days later, I drove Mark home.

Mark’s medical journey was first captained by an oncologist, then ENT and neurosurgeons, and now the epileptologist, Dr. F, has the command. It’s her position, as an epilepsy doctor, that seizures are 1) bad for the brain, and 2) bad for Mark, what with the partial skull situation and the incredibly high risk for falls. She’s exhausted medications for controlling Mark’s epilepsy, and therefore the only other option to pursue is surgery. On Monday, Dr. F will present Mark’s case to a medical board composed of eight epileptologists and a sprinkling of other -ologists, who will determine whether Mark has the potential to be a candidate for surgery. If so, they may move Mark to a next step along the path of data collection around his brain activity and structure. Phase Two, they will call it. And after Phase 2, they will give a final determination on the feasibility of surgery.

Or, on Monday, the board may determine surgery is not an option, closing the book on another chapter in this story.

Don’t worry, everyone. I am clear-headed about another surgery. I hope they don’t recommend it, because once again I do not want to have to make a decision. And I certainly don’t relish the idea of another surgery. In fact, I hate it. It makes me want to lay down in the forest, wait for autumn, and let the leaves cover me. Only if there is a high potential for an improvement in Mark’s quality of life, or further danger to his brain by not doing it, would I remotely consider a surgery. “I’m okay with continuing with the data collection,” I told our PCP during a recent visit that was supposed to be for me. “But Dr. K, what do I do if they decide surgery benefits outweigh the risk? How will I know what to choose?”

His eyes locked with mine, and then he spoke what I already knew. “There will be no good decision.”

Currently, I am simply waiting for whatever comes next while keeping an open mind, reading a lot about epilepsy and treatments, and trying not to let stress about it get the best of me.

Last night my dear childhood friend Dorothy called. I had helped her son with his college application essay. She wanted me to know he was accepted to his first choice school. We caught up about her life, and she told me about her upcoming vacation abroad.

Shortly after we hung up, a bing announced a text from her. Dorothy had watched my Instagram story in which I had explained that after a night of seizures, Mark had an accident. This had only happened once before. Both times, in the middle of the night, he rinsed his pants and underwear in the sink and then threw them down the laundry chute.

Soiled clothes, soiled sink, soiled Mark, soiled laundry chute.

Everyone taking care of someone with dementia has these kinds of stories. Mostly, they are kept quiet. To protect the dignity of the person who is sick, obviously, but people, I am TIRED and we all live in a human body that ultimately cannot live forever. The reality is difficult. The body is beautiful and hard to care for. The person is loved despite it all. I need you to bear witness.

In her text, Dorothy apologized for sharing about her upcoming trip, kindly acknowledging that my life cannot include these things. I have had this experience before, someone sharing something good with me and then quickly apologizing for it.

It’s okay, I urge you. It. Is. Okay.

“You live big out there for me,” I responded. And I mean that. My world is tiny in every way, and Mark’s sickness creates an event horizon that tries to suck all the light and energy from me. If you are a safe distance from your own personal black hole, I am SO HAPPY FOR YOU. Tell me all about it! Let me remember, and let me dream. By and large, I am okay. I find my ways.

Last week, Mark developed a new problem of low sodium caused by one of his seizure meds. To take him off the seizure med is to risk more seizures. To keep him on the seizure med without addressing the sodium problem is to risk brain swelling. The epileptologist asked me to ask the PCP to manage it. The PCP said he wants a nephrologist to handle it. And on and on we go, barreling down a new avenue on this journey.

While waiting for the nephrology appointment in June, I’m trying to add more salt into Mark’s diet. Cooking all his meals from scratch, as I do, is not the best way to load up on sodium, so the other day I took Mark to the McDonald’s drive through. I ordered him a double quarter pounder with cheese with Big Mac fixings, and I asked for a Filet-O-Fish.

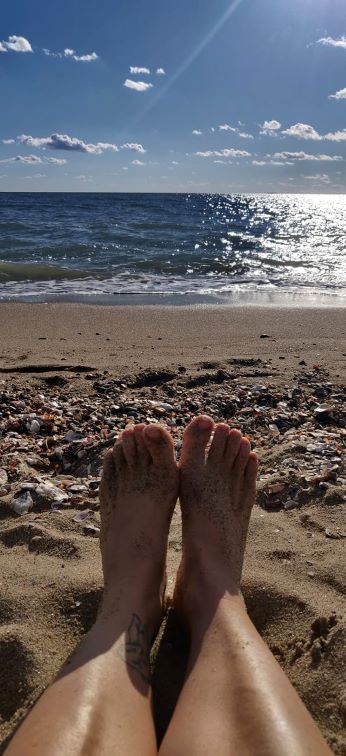

When I was growing up in Philadelphia, my family took summer trips to the Jersey shore. Crossing from the mainland to the island and entering Ocean City, we would often go through the McDonald’s drive-through, a special treat. I always ordered a Filet-O-Fish, the taste of it mingling with the salt air through the open station wagon windows, the promise of a day at the beach so close at hand.

Pulling out of the drive-through with Mark, I took a bite of my sandwich and allowed myself to picture that I was at the Jersey shore, the wind and water and waves nearby. I went there in my mind. It was good. It was enough.

It’s been steadily raining today. From my couch perch, I can watch Mark while gazing at the huge swaths of springtime green outside the front and back windows. Mark has the heat on, but I’ve discreetly opened a window so I can listen to the rain and birds. The clear, bold whistle of the white-throated sparrows, dominating the early morning soundscape for weeks now, has given way to the throaty trills of white-crowned sparrows tucked among the trees. Titmice call from the nearby hillside, and the occasional red-winged blackbird announces its presence at the feeder with loud shrieks. Mark sleeps. His muscles periodically twitch and jerk, the sides of his mouth pulling up in a smile that is not a smile. Bob the Pandemic Puppy is perched on the back of a chair, watching the world outside. It is quiet. “It all comes in waves,” a new Instagram friend, taking care of her mom with dementia, quoted her mom saying. “Ominous wisdom,” she tacked on.

Ominous or hopeful? It’s a fair question.