This is a medical update, and will read as such. It’s a lot. Read at your own risk.

Good news: Mark’s CT scans at the end of December were good – no cancer from belly to brain. Bad news: he has developed an infection in his head, and he will have surgery on Monday.

Let me give you an overview of the structure of Mark’s head. The original craniotomy (1.5 years ago) was done by removing a large section of the front of Mark’s skull, doing the needed work, and bracketing it back into place. You can’t see any scars on Mark’s head because they made the incision ear to ear, which is behind his hair line. In photos, the circular outline you can see from his forehead to the top of his head is where they removed and replaced that part of his skull.

There are other “dents, ditches and divots” as we call them related to Mark’s multiple craniotomies. Mark often runs his hands over his head and rests his fingers in them, like he’s finding the holes in a bowling ball. One dent makes it look like he was shot in the forehead with a BB gun. It’s a little off center and above his right eye. This is where, in August, after opening up Mark’s head from ear to ear again, the surgeon drilled a little hole in Mark’s skull in order to access and remove some dead brain tissue from his frontal lobe. During that surgery, they also removed part of Mark’s brow bone. They did this in order to access the area where the had to take out the damaged skull base and replace it with a tissue graft (from his leg and stomach). When they put the brow bone back in place, they put a graft behind that with the goal that it would vascularize and provide a blood supply to the area.

Still with me?

In December, that BB gun dent began to go from normal skin color to red. It didn’t hurt, Mark said, and he didn’t have any other symptoms. I emailed the neurosurgeon and sent pictures, and they took a watch and wait approach. Over the past week, Mark started to tell me that his head hurt at that dent whenever he blew his nose (which he does a lot because of his sinus graft still healing). The red spot seemed bigger to me. I emailed a photo to the neurosurgeon, and on Tuesday we went in to get it checked.

The surgeon said this is a complication that he suspected might happen. He pulled up scans, one post surgery showing where the graft behind the brow bone had been placed, and a more recent scan indicating that the graft was gone. It had not vascularized. A potential the neurosurgeon knew, because radiated tissue has a decreased ability to heal. The graft had been reabsorbed by Mark’s body, leaving an air pocket behind Mark’s brow bone. The brow bone died. The air pocket connects to Mark’s sinuses. “Bugs from the sinuses have gotten up there,” the neurosurgeon said. “Bugs love to feed on dead bone. We have to take the bone out.” So. An infection. Between his skull and the dura of the brain. The neurosurgeon said it was not an emergency. Then he said he wanted to admit Mark directly to the hospital.

You know how well Mark works in these situations, right? Not well. He refused. Refused any logical arguments about his health. His kids. Insurance processes if he came in other than a direct admit. The guy DUG IN. “Mark, if you were saying you were done, and didn’t want to try anymore, I’d support that,” I said. “But you are saying you want to keep fighting, for your kids in part. I am trying to support that.” Nope, nope, nope.

We went home. The surgery is scheduled for Monday. I feel a little like I did when a nurse, after an exhausting labor, handed me my first baby. “Why would you think I know what to do with this?!” I am watching him closely for signs of the infection spreading.

The surgery should take about two hours. This is another craniotomy. They will make an incision from ear to ear again. Peel back the skin. Do the thing. Put Mark back together. While they have him opened up, the ENT surgeon will take a peek at the sinus graft which we’ve only been able to see from the outside (up the nose with a scope) view. If they see anything they don’t like (lack of healing, dead tissue in the graft), then we go down yet another surgical pathway. He should be in the hospital for at least a few days, and then come home. I’m not worried about a cognitive dip from this, if everything goes as planned. I’m aware everything may not go as planned.

Final thoughts. Well. For now, Mark has remained fairly visually intact. Yes, he is thin. Yes, he has a few dents, ditches and divots. For this, they are not replacing the brow bone with a prosthetic. The neurosurgeon said Mark’s best bet is to having living tissue against living tissue: his skin directly laying on his dura. He will be disfigured, and it will be an adjustment for him, for the boys, and for me. I am tempted to dive into researching the strength of dome shapes, as I know that they are used for a reason in nature and architecture. We are removing more of Mark’s dome. What does that mean? Do I want to know? Could I know?

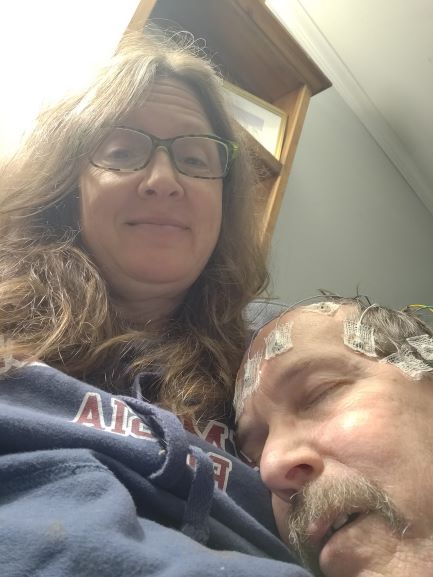

Mark is still “visiting,” as I said in an earlier post. That means he’s pretty with it. It means that he knows what he’s in for enough to be scared, and that’s hard to see. “I’m under threat,” he said, as he requested we stop on the way home from the hospital for a box of wine. Well, yes, you are.

Here’s a picture of Mark this morning, taking care of Robert who got a very short haircut. He wraps Robert up and gently pets him, taking care of what he can during these difficult days.

Send up a few prayers to the universe for us, if you have a moment. We are headed for the top of the rollercoaster again.