….and the time and energy to write disappeared. Here’s a quick update, minus creativity. Mark is home. The amount that he’s changed over the last three weeks is incredible. Three weeks ago, he could not spell the word “world” backwards. Two weeks ago, I watched him lean over to zip up his winter jacket and was amazed to see that he could do it. Today, I watched him write down a note about his breakfast intake, and he correctly remembered the day of the week — Saturday. He is thin and tired and also so much stronger as his body and brain recover from a brutal treatment protocol that seemed, without exaggeration, like it almost killed him.

A fairly comfortable daily pattern has evolved. Bobby arrives by 6:45 every morning and off I go. Bobby rotates through and exercise plan that he creates for Mark everyday: resistance bands, free weights, stairs, balance exercises, mental exercises like playing cards. Bobby exhibits beautiful intuitiveness about when to nudge Mark to do more or back off and let him rest with a “you’re the boss. I’m your friend. I’m not here to hurt you, I’m here to help you.” He makes sure Mark stays hydrated. He gives Mark feedings through his feeding tube as needed, and eats breakfast and lunch alongside Mark. In the afternoons, Bobby stays until a friend or my parents come over, or until I come home. I make dinner for the family. Mark and I watch Jeopardy. I give Mark a feeding through the feeding tube. A “bolus,” it’s called, but Mark somehow can’t hold onto that word and keeps calling it a “botus.” Beverage Of The United States? I set up his meds for the next day, we count his daily calories to see if he’s hit the minimum of 2000 (he’s really good at only hitting 1700-1800), and I go over the next day’s schedule with him, which he writes on a tabletop white board so he can refer to it the next day. I walk him back to the bedroom by 8pm and make sure the bedside commode is clean and that he’s safely in bed. I’m usually not that far behind him in calling it a day.

Mark’s brain is much more online than it’s been since about last June. This is a blessing, of course. It also means that Mark is really experiencing his illness, cognitively, for the first time. I ask him what he’s thinking about as he stares off into the distance, and more often now he’ll say “the possibilities of my life” or “mortality.” He lost his balance on Wednesday and got a little gash over his eye; this super scared him, even though Bobby was right there and caught him on the way down. Mark had been starting to push against the need to have someone with him at all times. But after the fall, Mark didn’t want to leave the house because he was newly alert to how his legs can feel weak and give out at anytime. Let alone the potential for seizures (which he still has periodically). He started using his walker to get to the bathroom or the bedroom or the kitchen.

I have continued to get calls, so many calls, about his care. Nurses, insurance, PT, OT, and speech. Two evenings ago a nurse called to check on him. We went over the equipment we have and don’t have. I thought we had it all: a wheelchair, the bedside commode, a blood pressure guage, feeding tube supplies, pill organizers, a regular standing-only walker and, arriving soon, a walker with a seat. “You don’t have a hospital bed,” she pointed out. Not there yet, I said.

Today, we had our first outing with the wheelchair. Mark wanted to go to Aldi with me; it was his idea to bring the chair. We maneuvered through the store successfully, equipped with a shopping cart, a wheelchair, a just-in-case a vomit bag and a bottle of seizure-stopping medication. A tiny stressful for me as I pushed the loaded cart while he foot-paddled his way down the slight incline to the parked car. We came home and took a long nap.

Mark’s treatments are finished for now. We are in a time period of healing and recovering. His Big Scan will be in mid-April. It will tell us all we need to know, we hope, about the efficacy of the treatment. A fork in the road. Another one.

I woke up early today to drive Matthew to the high school for a speech and debate tournament. Then Mark and I had coffee on the couch while I finished my latest murder mystery novel (I’m in a rut) and he read last week’s NYT Sunday Review, the news so dated after this week’s massive coronavirus scare and the shrinking of the Dem primary pool. I watched him read, stunned that he had the vision, cognitive capacity, and energy to read multiple articles. The changes keep coming, and some days — despite all we’ve been through — I find myself thinking it’s going to just continue to be a steady improvement. Bobby reminds me that this is just like in AA and NA recovery: “Sometimes it’s three steps forward, a half step back, Di.”

Today at breakfast I said to Mark, “how’s your nausea?” “Am I an alligator?” he said, repeating what he thought he had heard. “Did you really think that’s what I asked?” I laughed. “Yes,” he said.

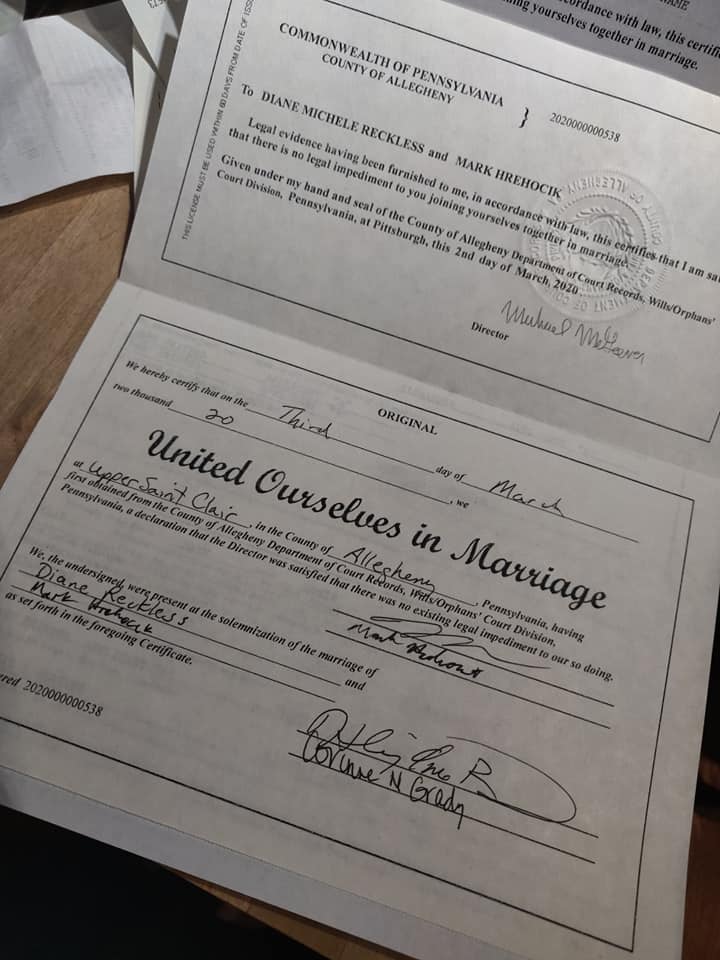

That’s my husband, ya’ll. If you look at the photo, you will see he has taken out his wallet so he can pay. Because that’s the kind of man he is, the guy who wants to take care of me.

What is marriage? What is a partnership? For better or for worse. For richer or for poorer. In sickness and in health.

I’ve got this. I’ve got him.